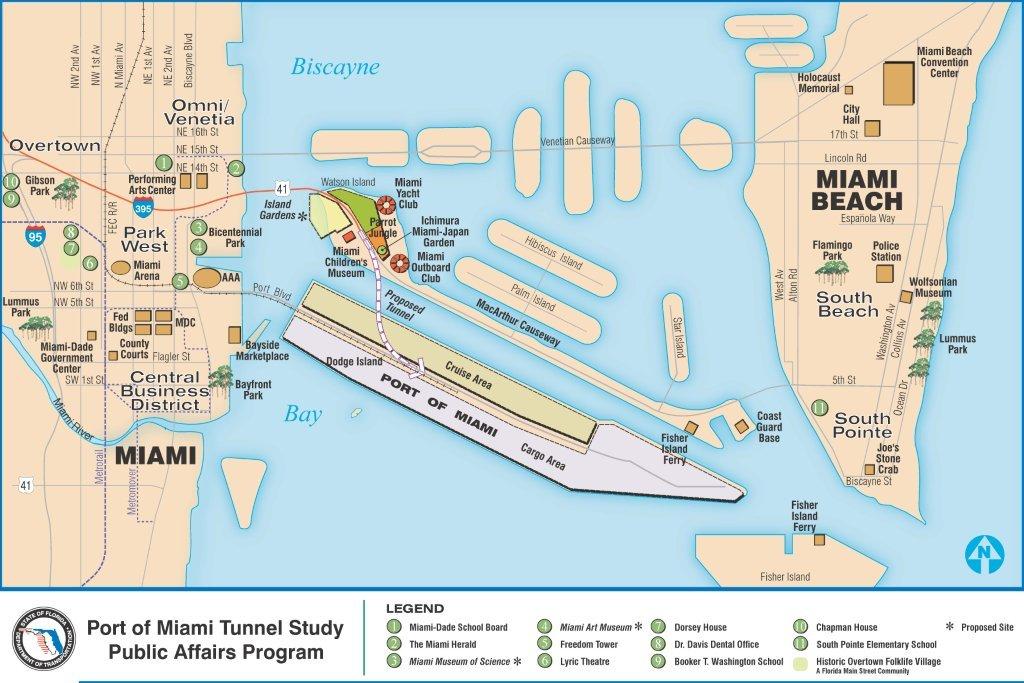

THE ANSWER: The Port of Miami Tunnel (POMT) – a $1 billion tunnel connecting I-395 to the Port of Miami.

THE DILEMMA: How exactly does one build a tunnel (twin tunnels actually) approximately 4,2000 feet long, almost 40 feet in diameter, and 120 feet below the surface of the water?

Enter “Harriet” – the $45 million German-built Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM) that has spent the past 18 months digging through the earth near Miami, leaving twin tunnels in her wake. The massive TBM that would build this underground network was aptly named, by the Miami-Dade County Girl Scouts, after Harriet Tubman.

Harriet was built and tested by Herrenknecht in Germany, then disassembled and packed for her transatlantic voyage to the U.S. in the Summer of 2011. Harriet is the largest diameter soft ground tunnel boring machine in the United States. In an assembled state, she is 428.5 feet long and her cutter head has an outside diameter of 42.3 feet. That’s longer than a football field and as high as a 4 story building.

The process for excavating and building the twin tunnels is not an easy one – even for Harriet. The “Tunneling Process” is described as follows:

The cutter head rotates as a cutting wheel boring out the underground area, while the trailing gear contains the electrical, mechanical, guidance systems and additional support equipment. Excavated material is carried back through the trailing gear on an enclosed conveyor belt and deposited outside the tunnel entrance, or portal. It is moved off‐site to be used as fill material and is disposed in a manner consistent with applicable environmental rules and regulations. As the TBM moves forward it erects precast concrete liners (known as segments) that become the finished wall of the tunnel. Once the liners are in place, grout is pumped into the space between it and the excavated area to fill any voids or gaps.

And about those “segments” that become the finished wall of the tunnel – it takes 8 segments to construct each ring and Harriet can construct 3-6 rings per day. According to the POMT website, “Harriet launched from her home in the Watson Island pit on November 11, 2011, boring the first tunnel towards Dodge Island. Harriet emerged on Dodge Island on July 31, 2012 where she was disassembled, turned and reassembled.” EarthCam captured Harriet’s breakthrough on Dodge Island on video.

Yesterday, May 6, 2013, Harriet reached the end of her journey. After working 24 hours a day (with 4 hours being for daily maintenance) with up to 30 people inside and on the machine’s surface – Harriet has finally reached the light at the end of the tunnel. To quote Chris Hodgkins, V.P. of Miami Access Tunnel: “She’s dirty, she’s worn, she’s missing a lot of her teeth. She wants to breathe some fresh air. She served us well, and she’s ready to call it a day.”

The Port of Miami Tunnel is expected to open to traffic in May 2014. For more information, visit the Port of Miami Tunnel website.

Don’t worry. That shaking you feel isn’t an earthquake. It’s the construction of the new Tappan Zee bridge across the Hudson River north of New York. I’m kidding of course. Construction on the $3.9 billion project hasn’t even started yet, but much of the geotechnical work, not to mention the design, has. Now they are planning on picking up good vibrations with highly sophisticated shoebox-sized sensors posted around the construction site. This is nothing new, but

Don’t worry. That shaking you feel isn’t an earthquake. It’s the construction of the new Tappan Zee bridge across the Hudson River north of New York. I’m kidding of course. Construction on the $3.9 billion project hasn’t even started yet, but much of the geotechnical work, not to mention the design, has. Now they are planning on picking up good vibrations with highly sophisticated shoebox-sized sensors posted around the construction site. This is nothing new, but